Hannah Glasseã¢ââ¢s ââåthe Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy

Frontispiece and championship folio in an early on posthumous edition, published by L. Wangford, c. 1777 | |

| Author | "By a LADY" (Hannah Glasse) |

|---|---|

| Country | England |

| Linguistic communication | English language |

| Discipline | English cooking |

| Genre | Cookbook |

| Publisher | Hannah Glasse |

| Publication appointment | 1747 |

| Pages | 384 |

The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy is a cookbook by Hannah Glasse (1708–1770) first published in 1747. It was a bestseller for a century after its outset publication, dominating the English-speaking market and making Glasse one of the most famous cookbook authors of her time. The book ran through at to the lowest degree 40 editions, many of which were copied without explicit author consent. It was published in Dublin from 1748, and in America from 1805.

Glasse said in her note "To the Reader" that she used plain language so that servants would exist able to understand information technology.

The 1751 edition was the first book to mention trifle with jelly as an ingredient; the 1758 edition gave the first mention of "Hamburgh sausages" and piccalilli, while the 1774 edition of the volume included ane of the first recipes in English for an Indian-style curry. Glasse criticised French influence of British cuisine, but included dishes with French names and French influence in the volume. Other recipes use imported ingredients including cocoa, cinnamon, nutmeg, pistachios and musk.

The book was pop in the Thirteen Colonies of America, and its appeal survived the American War of Independence, with copies being owned by Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson and George Washington.

Book [edit]

The Art of Cookery was the dominant reference for domicile cooks in much of the English-speaking world in the second half of the 18th century and the early 19th century, and information technology is still used as a reference for food research and historical reconstruction. The book was updated significantly both during her life and after her death.

Hannah Glasse'south signature at the top of the first chapter of her book, sixth Edition, 1758, in an attempt to reduce plagiarism

Early on editions were not illustrated. Some posthumous editions include a decorative frontispiece, with the caption

The Fair, who's Wise and often consults our BOOK,

And thence directions gives her Prudent Melt,

With CHOICEST VIANDS, has her Table Crown'd,

And Wellness, with Frugal Ellegance is constitute.

Some of the recipes were plagiarised, to the extent of being reproduced verbatim from earlier books by other writers.[i] To guard confronting plagiarism, the title page of, for example, the 6th edition (1758) carries at its pes the warning "This BOOK is published with his MAJESTY'south Regal Licence; and whoever prints it, or any Function of information technology, will be prosecuted". In addition, the starting time page of the main text is signed in ink by the author.

The first edition of the book was published by Glasse herself, funded by subscription, and sold (to non-subscribers) at Mrs. Ashburn's China Shop.[two]

Contents [edit]

- Chapter 1: Of Roasting, Boiling, &c.

- Chapter 2: Made Dishes.

- Affiliate three: Read this Chapter, and you will find how expensive a French Melt'due south Sauce is.

- Affiliate four: To make a Number of pretty piddling Dishes fit for a Supper, or Side-Dish, and little Corner-Dishes for a Great Table; and the balance you take in the Chapter for Lent.

- Chapter 5: Of Dressing Fish.

- Chapter 6: Of Soops and Broths.

- Affiliate vii: Of Puddings.

- Chapter 8: Of Pies.

- Chapter 9: For a Fast-Dinner, a Number of practiced Dishes, which yous may brand use of for a Table at any other Time.

- Chapter 10: Directions for the Sick.

- Affiliate 11: For Captains of Ships.

- Chapter 12: Of Hogs Puddings, Sausages, &c.

- Chapter thirteen: To pot and make Hams, &c.

- Chapter 14: Of Pickling.

- Chapter fifteen: Of making Cakes, &c.

- Chapter 16: Of Cheesecakes, Creams, Jellies, Whipt Syllabubs, &c.

- Affiliate 17: Of Made Wines, Brewing, French Staff of life, Muffins, &c.

- Chapter 18: Jarring Cherries, and Preserves, &c.

- Affiliate 19: To brand Anchovies, Vermicella, Catchup, Vinegar; and to go on Artichokes, French Beans, &c.

- Chapter 20: Of Distilling.

- Chapter 21: How to market, and the Seasons of the Year for Butchers Meat, Poultry, Fish, Herbs, Roots, &c and Fruit.

- Chapter 22: [Against pests]

- Additions

- Contents of the Appendix.

Approach [edit]

To make a trifle. [a] COVER the bottom of your dish or bowl with Naples biscuits bankrupt in pieces, mackeroons broke in halves, and ratafia cakes. Just moisture them all through with sack, then make a good boiled custard not also thick, and when cold pour information technology over it, so put a syllabub over that. You may garnish it with ratafia cakes, currant jelly, and flowers.[4]

The book has a brief tabular array of contents on the title page, followed by a annotation "To the Reader", and then a full list of contents, past chapter, naming every recipe. There is a full alphabetical index at the dorsum.

Glasse explains in her note "To the Reader" that she has written simply, "for my Intention is to instruct the lower Sort", giving the example of larding a chicken: she does non call for "large Lardoons, they would non know what I meant: But when I say they must lard with little Pieces of Salary, they know what I hateful." And she comments that "the great Cooks have such a high mode of expressing themselves, that the poor Girls are at a Loss to know what they mean."[5]

As well as simplicity, to suit her readers in the kitchen, Glasse stresses her aim of economy: "some Things [are] so extravagant, that it would be near a Shame to brand Use of them, when a Dish can be made full every bit skilful, or meliorate, without them."[6]

Chapters sometimes brainstorm with a brusk introduction giving full general advice on the topic at hand, such every bit cooking meat; the recipes occupy the rest of the text. The recipes give no indication of cooking fourth dimension or oven temperature.[7] In that location are no carve up lists of ingredients: where necessary, the recipes specify quantities direct in the instructions. Many recipes practise not mention quantities at all, only instructing the cook what to exercise, thus:

Sauce for Larks. LARKS, roast them, and for Sauce take Crumbs of Staff of life; done thus: Have a Sauce-pan or Stew-pan and some Butter; when melted, have a expert Piece of Nibble of Bread, and rub it in a make clean Cloth to Crumbs, and so throw it into your Pan; keep stirring them nearly till they are Brownish, then throw them into a Sieve to drain, and lay them round your Larks.[8]

Foreign ingredients and recipes [edit]

Glasse used plush truffles in some recipes.

Glasse set out her somewhat critical[nine] views of French cuisine in the book's introduction: "I accept indeed given some of my Dishes French Names to distinguish them, because they are known past those names; And where in that location is not bad Variety of Dishes, and a big Table to encompass, so in that location must exist Diverseness of Names for them; and it matters not whether they exist called past a French, Dutch, or English Name, then they are skillful, and washed with as trivial Expence as the Dish volition allow of."[10] An example of such a recipe is "To à la Daube Pigeons";[11] a daube is a rich French meat stew from Provence, traditionally made with beefiness.[12] Her "A Goose à la Mode" is served in a sauce flavoured with ruby-red wine, domicile-made "Catchup", veal sweetbread, truffles, morels, and (more ordinary) mushrooms.[xiii] She occasionally uses French ingredients; "To make a rich Cake" includes "half a Pint of correct French [b] Brandy", besides equally the aforementioned amount of "Sack" (Spanish sherry).[13]

Successive editions increased the number of not-English recipes, calculation German, Dutch, Indian, Italian, W Indian and American cuisines.[14] The recipe for "Elder-Shoots, in False of Bamboo" makes use of a homely ingredient to substitute for a foreign one that English language travellers had encountered in the Far Due east. The same recipe too calls for a multifariousness of imported spices to flavour the pickle: "an Ounce of white or scarlet Pepper, an Ounce of Ginger sliced, a piffling Mace, and a few Corns of Jamaica Pepper."[xv]

There are two recipes for making chocolate, calling for plush imported ingredients like musk (an effluvious obtained from musk deer) and ambergris (a waxy substance from sperm whales), vanilla and cardamon:[xvi]

Take 6 pounds of Cocoa-nuts, One Pound of Anniseeds, iv Ounces of long Pepper, ane of Cinnamon, a Quarter of a Pound of Almonds, 1 Pound of Pistachios, as much Achiote[c] as will make information technology the colour of Brick; three grains of Musk, and as much Ambergrease, six Pounds of Loaf-sugar, one Ounce of Nutmegs, dry and beat them, and fearce them through a fine Sieve...[xvi]

Reception [edit]

Contemporary [edit]

England [edit]

Ann Cook used the platform of her 1754 book Professed Cookery to launch an aggressive attack on The Art of Cookery.[17]

The Art of Cookery was a bestseller for a century afterwards its first publication, making Glasse one of the most famous cookbook authors of her fourth dimension.[18] The book was "by far the most popular cookbook in eighteenth-century Britain".[19]

It was rumoured for decades that despite the byline information technology was the piece of work of a human, Samuel Johnson being quoted by James Boswell as observing at the publisher Charles Dilly'southward business firm that "Women can spin very well; simply they cannot brand a good volume of cookery."[18]

In her 1754 book Professed Cookery, Glasse'south contemporary Ann Cook launched an ambitious assault on The Art of Cookery using both a doggerel poem, with couplets such as "Look at the Lady in her Title Page, How fast it sells the Book, and gulls the Age",[20] and an essay; the poem correctly accused Glasse of plagiarism.[17] [20]

The Foreign Quarterly Review of 1844 commented that "there are many good receipts in the piece of work, and it is written in a obviously mode." The review applauds Glasse'south goal of plain linguistic communication, but observes "This book has ane great fault; it is disfigured by a strong anti-Galician [anti-French] prejudice."[21]

Thirteen Colonies [edit]

The book sold extremely well in the Colonies of North America. This popularity survived the American War of Independence. A New York memoir of the 1840s declared that "We had emancipated ourselves from the sceptre of Rex George, but that of Hannah Glasse was extended without claiming over our fire-sides and dinner-tables, with a sway far more imperative and absolute".[19] The starting time American edition of The Art of Cookery (1805) included two recipes for "Indian pudding" too as "Several New Receipts adjusted to the American Manner of Cooking", such as "Pumpkin Pie", "Cranberry Tarts" and "Maple Sugar". Benjamin Franklin is said to accept had some of the recipes translated into French for his cook while he was the American ambassador in Paris.[22] [23] Both George Washington and Thomas Jefferson owned copies of the book.[24]

Food critic John Hess and food historian Karen Hess have commented that the "quality and richness" of the dishes "should surprise those who believe that Americans of those days ate simply Spartan borderland food", giving every bit examples the glass of Malaga wine, seven eggs and half a pound of butter in the pumpkin pie. They argue that while the elaborate bills of fare given for each month of the year in American editions were conspicuously wasteful, they were less and then than the "interminable" menus "stuffed down" in the Victorian era, as guests were not expected to consume everything, but to choose which dishes they wanted, and "the cooking was demonstrably better in the eighteenth century."[22]

The book contains a recipe "To make Hamburgh Sausages"; it calls for beef, suet, pepper, cloves, nutmeg, "a great Quantity of Garlick cut minor", white wine vinegar, salt, a glass of red wine and a glass of rum; once mixed, this is to exist stuffed "very tight" into "the largest Gut you lot tin can find", smoked for up to ten days, and then air-dried; information technology would keep for a year, and was "very good boiled in Peas Porridge, and roasted with toasted staff of life under it, or in an Amlet".[25] The cookery author Linda Stradley in an article on hamburgers suggests that the recipe was brought to England by German immigrants; its appearance in the first American edition may exist the showtime time "Hamburgh" is associated with chopped meat in America.[26]

Modern [edit]

Rose Prince, writing in The Independent, describes Glasse as "the first domestic goddess, the queen of the dinner political party and the nearly important cookery writer to know nearly." She notes that Clarissa Dickson Wright "makes a good case" for giving Glasse this much credit, that Glasse had plant a gap in the market, and had the distinctions of simplicity, an "appetising repertoire", and a lightness of bear on. Prince quotes the nutrient writer Bee Wilson: "She's authoritative only she is besides intimate, treating you equally an equal", and concludes "A perfect book, then; one that deserved the acclaim it received."[27]

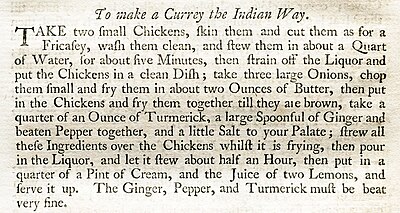

Receipt To brand a Currey the Indian Way, on page 101

The cookery writer Laura Kelley notes that the 1774 edition was one of the first books in English to include a recipe for curry: "To make a currey the Indian manner." The recipe calls for two modest chickens to be fried in butter; for ground turmeric, ginger and pepper to be added and the dish to exist stewed; and for cream and lemon juice to be added just before serving. Kelley comments that "The dish is very good, but not quite a modernistic curry. As you can see from the title of my interpreted recipe, the modern dish most like information technology is an eastern (Kolkata) butter chicken. Nevertheless, the Hannah Glasse curry recipe lacks a full complement of spices and the varying amounts of tomato plant sauce at present and then oftentimes used in the dish."[28]

The cookery writer Sophia Waugh said that Glasse's food was what Jane Austen and her contemporaries would have eaten. Glasse is ane of the five female writers discussed in Waugh'due south 2013 book Cooking People: The Writers Who Taught the English How to Eat.[29]

The cookery writer Clarissa Dickson Wright calls Glass's curry a "famous recipe" and comments that she was "a bit sceptical" of this recipe, as information technology had few of the expected spices, but was "pleasantly surprised past the end result" which had "a very skillful and interesting flavour".[30]

The historian of food Peter Brears said that the book was the starting time to include a recipe for Yorkshire pudding.[31]

Legacy [edit]

Ian Mayes, writing in The Guardian, quotes Brewer'south Dictionary of Phrase and Fable equally stating "Starting time take hold of your hare. This management is by and large attributed to Hannah Glasse, habit-maker to the Prince of Wales, and author of The Art of Cookery made Evidently and Easy". Her bodily directions are, 'Take your Hare when information technology is cas'd, and brand a pudding...' To 'example' means to take off the skin" [not "to catch"]; Mayes notes further that both the Oxford English language Lexicon and The Lexicon of National Biography talk over the attribution.[32]

As at 2015[update], Scott Herritt'south "South End" eating house in South Kensington, London, serves some recipes from the book.[33] The "Nourished Kitchen" website describes the effort required to translate Glasse's 18th-century recipes into modern cooking techniques.[7]

Editions [edit]

The book ran through many editions, including:[34]

- First edition, London: Printed for the author, 1747.

- London: Printed for the author, 1748.

- Dublin: East. & J. Exshaw, 1748.

- London: Printed for the author, 1751.

- London: Printed for the author, 1755.

- Sixth edition, London: Printed for the author, sold by A. Millar, & T. Trye, 1758.

- London: A. Millar, J. and R. Tonson, W. Strahan, P. Davey and B. Law, 1760.

- London: A. Millar, J. and R. Tonson, W. Strahan, T. Caslon, B. Law, and A. Hamilton, 1763.

- Dublin: Due east. & J. Exshaw, 1762.

- Dublin: E. & J. Exshaw, 1764.

- London: A. Millar, J. and R. Tonson, W. Strahan, T. Caslon, T. Durham, and W. Nicoll, 1765.

- London: W. Strahan and 30 others, 1770.

- London: J. Cooke, 1772.

- Dublin: J. Exshaw, 1773.

- Edinburgh: Alexander Donaldson, 1774.

- London: W. Strahan and others, 1774.

- London: L. Wangford, c. 1775.

- London: W. Strahan and others, 1778.

- London: Westward. Strahan and 25 others, 1784.

- London: J. Rivington and others, 1788.

- Dublin: W. Gilbert, 1791.

- London: T. Longman and others, 1796.

- Dublin: W. Gilbert, 1796.

- Dublin: W. Gilbert, 1799.

- London: J. Johnson and 23 others, 1803.

- Alexandria, Virginia: Cottom and Stewart, 1805.

- Alexandria, Virginia: Cottom and Stewart, 1812.

- London: H. Quelch, 1828.

- London: Orlando Hodgson, 1836.

- London: J.S. Pratt, 1843.

- Aberdeen: M. Clark & Son, 1846.

- The fine art of cookery, made apparently and easy to the agreement of every housekeeper, cook, and retainer. With John Farley. Philadelphia: Franklin Court, 1978.

- "Offset catch your hare--" : the art of cookery made plainly and like shooting fish in a barrel. With Jennifer Stead, Priscilla Bain. London: Prospect, 1983.

-

- --- Totnes: Prospect, 2004.

- Alexandria, Virginia: Applewood Books, 1997.

- Farmington Colina, Michigan: Thomson Gale, 2005.

- Mineola, New York: Dover Publications, 2015.

See also [edit]

- Cajsa Warg

- François Pierre La Varenne

- Early on modern European cuisine

Notes [edit]

- ^ This recipe first appeared in the 1751 edition, making Glasse the showtime writer to record the employ of jelly in trifle.[3]

- ^ Her emphasis.

- ^ Achiote is the establish that yields the natural paint annatto, still used to colour nutrient.

References [edit]

- ^ Rose Prince (24 June 2006). "Hannah Glasse: The original domestic goddess". The Contained. Archived from the original on 7 June 2010. Retrieved 6 March 2019.

- ^ Boyle, Laura (13 Oct 2011). "Hannah Glasse". Jane Austen Centre. Archived from the original on nine Oct 2014. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- ^ Phipps, Catherine (21 December 2009). "No such thing as a mere trifle". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 22 Dec 2015. Retrieved 20 Dec 2015.

- ^ Glasse, 1758. Page 285

- ^ Glasse, 1758. Page i

- ^ Glasse, 1758. Page ii

- ^ a b McGuther, Jenny (27 September 2009). "Cookery Made Patently & Easy – An 18th Century Supper". Nourished Kitchen. Archived from the original on 7 March 2018. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- ^ Glasse, 1758. Pages v–6

- ^ Dickson Wright, Clarissa (2011). A History of English Nutrient (First ed.). Random Business firm. p. 298. ISBN978-1905211852.

- ^ Glasse, 1758. Page five

- ^ Glasse, 1758. Page 85

- ^ "Daube de boeuf provençale, la recette". Saveurs Croisees. Archived from the original on 19 March 2015. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- ^ a b Glasse, 1758. Page 271

- ^ Bickham, Troy (February 2008). "Eating the Empire: Intersections of Food, Cookery and Imperialism in Eighteenth-Century United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland". Past & Present. 198 (198): 71–109. doi:10.1093/pastj/gtm054. JSTOR 25096701.

- ^ Glasse, 1758. Page 270

- ^ a b Glasse, 1758. Page 357

- ^ a b Monnickendam, Andrew (2018). "Ann Cook versus Hannah Glasse: Gender, Professionalism and Readership in the Eighteenth‐Century Cookbook". Journal for Eighteenth-Century Studies. 42 (2): 175–191. doi:10.1111/1754-0208.12606. ISSN 1754-0194. S2CID 166028026.

- ^ a b "The Art of Cookery". British Library. Archived from the original on 17 March 2015. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- ^ a b Stavely, Keith Due west. F.; Fitzgerald, Kathleen (1 January 2011). Northern Hospitality: Cooking by the Volume in New England. Univ of Massachusetts Press. p. eight. ISBN978-1-55849-861-seven. Archived from the original on 4 July 2016. Retrieved 8 July 2016.

- ^ a b Lehmann, Gilly (2003). The British Housewife: Cooking and Guild in 18th-century Britain. Totness, Devon: Prospect Books. pp. 114–117. ISBN978-ane-909248-00-seven.

- ^ The Foreign Quarterly Review. Treuttel and Würtz, Treuttel, Jun, and Richter. 1844. p. 202.

- ^ a b Hess, John L.; Hess, Karen (2000). The Gustatory modality of America. University of Illinois Press. p. 85. ISBN978-0-252-06875-1.

- ^ Chinard, Gilbert (1958). Benjamin Franklin on the Art of Eating. American Philosophical Club. p. (cited by Hess and Hess, 2000).

- ^ Rountree, Susan Hight (2003). From a Colonial Garden: Ideas, Decorations, Recipes. Colonial Williamsburg. p. i. ISBN978-0-87935-212-7.

- ^ Glasse, 1758. Page 370.

- ^ Stradley, Linda (2004). "Hamburgers - History and Legends of Hamburgers". What'due south Cooking America. Archived from the original on 22 March 2015. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- ^ Prince, Rose (24 June 2006). "Hannah Glasse: The original domestic goddess". The Independent. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- ^ Kelley, Laura (fourteen Apr 2013). "Indian Curry Through Strange Eyes #1: Hannah Glasse". Silk Route Gourmet. Archived from the original on 6 February 2018. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- ^ "Centuries of home cooking inspiration from female writers to be brought to life at Hampshire's Sophia Waugh book event". Hampshire Life. 4 February 2014. Archived from the original on 29 March 2021. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- ^ Dickson Wright, Clarissa (2011). A History of English Food. Random House. pp. 304–305. ISBN978-1-905-21185-2.

- ^ "Yorkshire pudding wrap: Reinventing the humble delicacy". BBC Leeds & W Yorkshire. 22 September 2017.

According to Yorkshire nutrient historian Peter Brears, the recipe showtime appeared in a book called The Fine art Of Cookery by Hannah Glasse in 1747. She *whisper* came from Northumberland.

- ^ Mayes, Ian (3 June 2000). "Splitting Hares". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 3 April 2015. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- ^ Kummer, Corby (November 2012). "Restaurant Review: Kitchen in the South End". Boston Mag. Archived from the original on two April 2015. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- ^ "Hannah Glasse: Art of Cookery". WorldCat. Archived from the original on 29 March 2021. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

External links [edit]

- In various formats at the Cyberspace Annal

-

The Art of Cookery Made Obviously and Easy public domain audiobook at LibriVox

The Art of Cookery Made Obviously and Easy public domain audiobook at LibriVox

wilkersontrablinever.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Art_of_Cookery_Made_Plain_and_Easy

Belum ada Komentar untuk "Hannah Glasseã¢ââ¢s ââåthe Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy"

Posting Komentar